Rules in Practice, part 3

The Rise of the ‘Traditional’ Style (1980s–1990s)

Read more of the Rules in Practice series

The Origins of “Traditional” Play

As tabletop RPGs gained popularity through the late 1970s and 1980s, the hobby evolved rapidly. One early major milestone was the publication of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (AD&D) 1st Edition (released 1977–1979).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, AD&D was far more detailed than the original D&D. Gary Gygax explicitly wrote it to standardize play and eliminate the ambiguities and divergent house rules that had arisen in the wild, although it would ultimately accomplish neither.

In Dragon magazine in 1979, Gygax even lamented that OD&D had “turned into a non-game” due to inconsistent local variations, promising that AD&D would provide “form and structure” so there’d be “no question in the mind of participants as to what the game is.”

This push for uniform rules did make AD&D a more rigid system, aiming to produce a more uniform style of play across tables, although in the process it introduced an expanding number of subsystems and irregular complexities that vastly increased the amount of time involved cross-referencing tables or the specific and often esoteric phrasing of various passages of text.

Along with AD&D, many new RPGs of the 1980s — from Call of Cthulhu to Traveller to Champions — arrived with thicker rulebooks and more formal procedures. Overall the rule sets became more comprehensive and mechanics-heavy, reflecting a trend toward codifying how the game should be played. The idea was that if everyone played by the same robust rules, everyone would be “playing the same game.”

Again, Gygax insisted AD&D be played Rules-As-Written (RAW) for consistency, whereas D&D was “free-wheeling”. As proposed, the Advanced edition would be a kind of Anti-Rule Zero RPG. Ironic, given what I’ve already discussed in part 2 of this series.

It would not go quite as planned. By the early 1980s, the style of play in many circles was shifting in a different direction — toward something that aimed at capturing a semblance of the increasingly popular fictional settings and stories of the time, a little more pre-scripted than the free-form dungeon crawling of the 1970s, utilizing the rules as a means of arbitrating elements of those narratives by way of gamism and simulation. (Gygax himself seemed quite opposed to simulation in several statements over the years despite using a great deal of it in the systems he co-created and used. This may have been a result of positioning re: the style of wargaming, which D&D evolved out of.)

This emerging dominant approach later retroactively came to be known as the “Traditional” (or Trad) culture of play. This style was reinforced by the RPG products of the era. The 1980s saw a kind of Cambrian explosion of rich campaign settings and epic adventure modules, and novels that added to the fictional lore of those specific settings. The settings themselves became increasingly elaborate, to the enjoyment of some and consternation of others.

This anecdote is telling in terms of the origins of Trad, and how it was increasingly distinct from the “classic” style:

“...The defining incident for Tracy was evidently running into a vampire in a dungeon and thinking that it really needed a story to explain what it was doing down there wandering around. Hickman wrote a series of adventures in 1980 (the Night Verse series) that tried to bring in more narrative elements, but the company that was supposed to publish them went bust. So he decided to sell them to TSR instead, and they would only buy them if he came to work for them. So in 1982, he went to work at TSR and within a few years, his ideas would spread throughout the company and become its dominant vision of ‘roleplaying’.”

The Trad impulse began with asking why the vampire is there. A useful origin story, at least.

To flesh out the increasing scope and potential power of player characters in ongoing campaigns, various large-scale sub-systems also came into vogue.

Examples frequently cited as solidifying Trad values include TSR’s Dragonlance saga (modules and novels beginning in 1984) and the Ravenloft module (I6 Ravenloft, 1983). These products provided strong, structured narratives for Game Masters (GMs). For example, the Dragonlance adventure series (1984–86) consisted of fourteen linked modules forming the epic plot of the War of the Lance — a story essentially structured along the lines of the novels, which themselves were based on an actualplay campaign. In these modules, players didn’t even use personal characters but assumed pre-generated heroes like Tanis and Raistlin. This ensured dramatic beats might be triggered as intended along with unexpected twists, embedding players as contributors in their version of ongoing fan-fic. A novel based on a campaign, inspiring new campaigns. This became a fairly common model across systems and editions as the years passed, even though the order might change.

Rather than improvising entire worlds or plots, GMs could rely on detailed scripts provided by designers, or they could develop their own, either within the sandbox provided by the setting, or by cobbling together parts of those “official” resources with their own inventions. The Hickmans’ 1980 adventure design manifesto explicitly emphasized integrating plot and story into gameplay, laying the groundwork for Trad’s narrative-focused intent.

Repeated exposure to such modules influenced an entire generation of gamers, who internalized a distinct social contract: the GM crafted the storyline while players navigated challenges and overcame obstacles, typically within the context of a predefined setting.

Not that these trends were monolithic, as they occurred simultaneously and often side-by-side with discussions of increasingly expansive rules and rulings, and with tables continuing the previously discussed “Classic” play-style. As discussed in Part 1, it’s altogether possible to run different play styles with the same system, and it is likely that many different tables were doing very different things with AD&D 2E than running long-form campaigns. Nevertheless, despite all efforts, AD&D in no way slayed Rule Zero. (Perhaps they only made Rule Zero more powerful).

What is Trad? Some Commonalities, and Points of Divergence

Mechanically, Traditional-style games varied in rules “crunch.” Some Trad games like Shadowrun or GURPS were mechanically fairly heavy while others like World of Darkness were relatively lighter, at least in terms of the core resolution system.

The social contract in a Trad game often implied that the fun comes from engaging with the setting and the characters’ development within it, even when that development was most often expressed as their increasing control over it (“power”).

It’s worth recognizing that while that increase in capability may often be for its own sake, it also provides the opportunity for a shifting of narrative and setting scope, whereas characters might be involved in local threats and concerns at level one, they are engaged in broader concerns later — potentially even across entire worlds or planes of existence by the end of a campaign.

The rulebooks were extensive, but they were often treated as toolkits to be used or set aside as needed for the sake of a more satisfying outcome. This was a marked shift from the earlier days of the hobby, where, if one player’s character died in a trap five minutes into the session, “oh well, them’s the breaks.”

The phrase “role-playing, not roll-playing” became a mantra in these circles, signaling that portraying characters and advancing the plot was deemed more important than slavishly following mechanical die-roll results.

The GM was not a neutral referee: they were a director who ideally would make sure the narrative spotlight rotated to each protagonist in turn. Trad groups routinely house-ruled on the fly or selectively applied rules to maintain cohesion. While this was sometimes the result of group consensus, the GM remained the final arbiter.

The ethics of play had shifted. If a scene would be ruined by an unlucky die roll, a Trad GM might decide to bend the outcome behind the screen or devise a story-based reason to mitigate it. Fudging dice to save a hero was now often considered the “right” thing to do in a Trad campaign (especially if it was to preserve the story and emotional investment), whereas in an old-school game it might be seen as cheating or robbing the game of its challenge.

We’ll revisit this idea of different “ethical frameworks” in play cultures in a later article, but it’s worth noting how distinct the Trad style’s unwritten rules were from those of the classic/OSR style. Here we see the interplay of system and style tilt strongly: in Trad play, the GM’s “campaign story” trumps rules whenever there’s a conflict.

Likewise, GMs in Trad style felt a new responsibility: to ensure each player’s character had an arc or at least some cool moments in the story. The idea of giving each character a “spotlight” moment started to become part of good GM practice in this era, although it is a frequently used format in various subsequent play styles as we discussed in Episode 10 of the Modern Mythology podcast. Focusing on this element above the others and centering the characters would become what distinguished the later “Neo-Trad” play style.

In Episode 8, we noted how applying conventional linear story structures to an RPG can lead to “railroading” (a typically pejorative term for when player choices are overly constrained to serve a pre-written plot). However, we focused on the myriad ways that GMs can use story structure in more open-ended ways to guide play without negating player agency. Even breaking a campaign into a linear arc of Acts needn’t be constraining, so long as it is broadly defined, and subject to change.

Structure can be a guiding mechanism in interactive stories just as much as in pre-determined ones (such as a novel). You could see early versions of this idea presented in the various methods that modules and setting materials introduced to move groups from an inciting incident to a resolution.

Trad games at their worst did railroad players, but at their best they delivered memorable, coherent arcs while still allowing player improvisation – a tricky balance that many groups strove to strike. Most notably, they introduced the idea that the stories that evolved from RPGs didn’t need to be the result of somewhat arbitrary procedural processes, as it had been in the “Classic” style. The systems methods of bringing this about still typically leaned pretty heavily on simulationism and gamism however, as we’ll explore in a moment.

It’s also worth emphasizing that plenty of Trad GMs did allow meaningful choices and twists. But it did mean that the expectation was different from the old sandbox days: a “good GM” should have a plot in mind and “good players” should cooperate by interacting with it rather than running in the opposite direction with a 10’ pole. Players who tried to do something radically off-script — say, kill a story-critical NPC on a whim or abandon the quest to pursue unrelated shenanigans — were typically seen as disruptive or not playing “right.”

The Height of an Era

By the early 1990s, the Trad style was pervasive in the RPG hobby. Even Dungeons & Dragons itself had fully embraced it: Advanced D&D 2nd Edition (1989) continued the trend with an emphasis on expansive settings and scenario play that were increasingly focused on the “campaign” and its story.

In fact, AD&D 2E’s legacy is largely defined by its proliferation of rich settings (Forgotten Realms, Dark Sun, Planescape, etc.) with narrative-heavy modules, at least on the NPC, lore and structure side. The game’s publishers at TSR leaned into this type of storytelling — hiring novelists, producing saga-style adventure arcs, and positioning the Dungeon Master more and more as an authorial figure.

“... If you ever hear people complain about (or exalt!) games that feel like going through a fantasy novel, that’s trad. Trad prizes gaming that produces experiences comparable to other media, like movies, novels, television, myths, etc., and its values often encourage adapting techniques from those media.” (Retired Adventurer).

Many (although not all) 2E products deemphasized pure dungeon crawls in favor of grand settings and the adventures they might provide, and most of the intentions that Gygax had stated for 1st edition AD&D were long since quietly swept away. For example, the Planescape setting (1994) was built around philosophical factions and epic quests, so much so that its designer Zeb Cook explicitly borrowed the idea of faction-based gameplay from White Wolf’s Vampire.

Reviews at the time praised Planescape’s story and worldbuilding — Pyramid magazine called it “the finest game world ever produced for AD&D”. In short, by the ’90s the industry leader D&D had fully incorporated the ethos of Trad play: more world, more character depth, more story, even as its rulebooks remained extensive and yet mostly barren of systems that directly engaged with story.

Many homebrew campaigns of this era adopted similar structures, or drew ad hoc from settings. Some modules supported that style of play better out of the box than others, although setting source materials became more ad hoc in the early 90’s.

Without going too in-depth into the troubled transition from TSR to WotC, it’s worth briefly mentioning how the internal tension we’ve been referring back to since the beginning of this series played some role in what would see the end of TSR as such.

One of TSR’s problems had become trying to design and market a single, coherent product line that could satisfy all the increasingly competing cultures of play that were on the rise in the 1980s. Whatever motivations based on game design philosophy may have been, the attempt to use AD&D to codify a single clearly delineated system might be seen as an attempt to move in this direction.

It’s a tough needle to thread. An adventure module written for a tactical group would feel restrictive and boring to a storytelling group while a new rulebook with complex, granular rules designed to close loopholes for power gamers would be seen as cumbersome and unnecessary by casual players, and so on.

This forced TSR into a reactive position. They were constantly trying to “keep up” with how people were actually playing their game, a game which, by the code they’d been involved in defining (Rule Zero), encouraged deviation and personalization. “Buy our new, official book of updated rules that you are officially allowed to ignore.”

Ultimately this would lead to edition wars, rules bloat, and a constant struggle to define what their own product actually was, partly because the core design empowered the user to redefine it at will. Other reasons had to do more with realities of the publishing industry at the time exacerbating the risks of growth, but this too had a lot to do with the misalignments of the vision, the system, and the actual cultures of play at work.

As they say, hindsight is 20/20. Yet all these years later, if the average person thinks of RPGs at all they think of Dungeons & Dragons, although TSR is no more. And WotC still (mostly) dominates the market.

Perhaps the clearest exemplars of the Traditional style came from White Wolf Publishing beginning in the early 1990s. White Wolf’s various World of Darkness games — starting with Vampire: The Masquerade (1991), followed by Werewolf: The Apocalypse (1992), Mage: The Ascension (1993), and others — expressly pushed for a story-first agenda.

While increasingly creative settings were the norm for 2nd edition AD&D releases, this overt centralization of drama was new. Vampire: The Masquerade was hailed by many as a watershed. It cast the players as tormented anti-heroes in a modern gothic-punk horror setting, dealing with personal tragedy and moral choices rather than looting treasure or slaying monsters. The Vampire rulebook explicitly encouraged an “expressive, character-driven” style of play, focusing on plots, intrigue, and character development over the straightforward combat challenges of traditional dungeon scenarios.

The Vampire community (especially its influential LARPs, such as Mind’s Eye Theatre) famously embraced the mantra of “mood, story, and personal horror” over dice and tactics. The official Vampire live-action rules minimized random mechanics (using simple comparisons or rock-paper-scissors for conflicts) specifically to keep players in an improvisational storytelling mode, not pausing for die-rolls.

White Wolf games styled their sessions as chapters in a chronicle, the GM as a “Storyteller”, and gaming groups often took on a quasi-theatrical approach — with elaborate backstories, in-character diary entries, and an expectation that everyone was collaboratively weaving an ongoing narrative. The Vampire rulebook’s introduction and essays talked about exploring themes of morality, the Beast within, the human condition, etc., which was a far cry from the casual “kick down the door” adventuring of classic D&D.

Yet, ironically, these more narrative-focused games still had extensive simulationist/gamist rule systems — despite their story-first goals, their actual books were not rules-light indies. The core system (d10 dice pools for attributes+skills) was fairly straightforward, but the overall line accumulated lots of complexity (numerous sourcebooks, powers, subsystems for things like humanity, frenzy, influence, etc.). The same was true for other Storyteller games. They were lighter than something like AD&D in some respects, but they weren’t minimalist, nor were they narrativist at the systems level.

The pattern remained: the systems had grown bigger over the years, but how those systems were used depended on group style. Many Vampire groups would freely ignore or streamline rules whenever those rules got in the way of the drama — a very Trad thing to do.

On the other hand, some groups did engage the mechanics heavily (for instance, focusing on dice-driven combat or min-maxing vampire powers), which led to some backlash that the World of Darkness games could degenerate into “roll-playing” despite the official stance.

This tension between the intended style (narrative, character-driven) and the mechanical reality (big rulebooks that could facilitate combat or other actions by simulation) became a topic of discussion in the late ’90s. It wasn’t uncommon to hear a White Wolf fan say their group mostly just told stories and ignored the dice, and in the same breath to hear a detractor quip that Vampire “always turns into a superpowered fight eventually.”

Both were probably true, depending on the table.

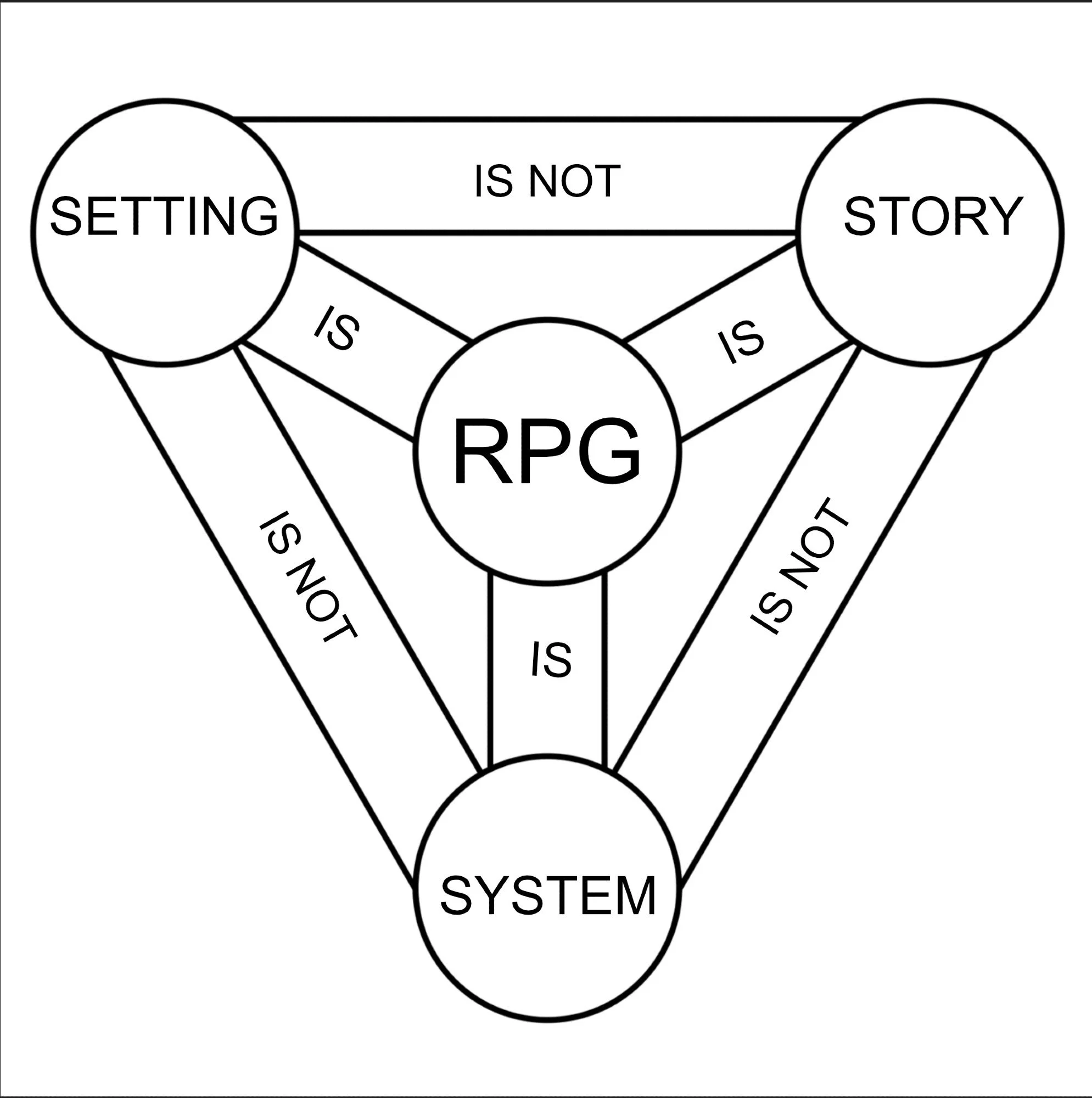

Story Games, but not “Story-Games”: Some Thoughts on GNS and Trad gaming

In Trad circles, the promise seemed clear enough: play to uncover a sweeping adventure set in a fictional world. The story, fictional world, or setting was a significant part of what attracted new players, notably from AD&D’s 2nd edition onward. Many, including myself, first encountered roleplaying games through novels rather than rulebooks.

However, the tools provided to achieve narrative goals were predominantly simulationist — driven by gamist reward loops — rather than rules directly framing theme or narrative structure. Rulebooks of the era dedicated extensive pages to movement rates, encumbrance, reaction tables, and even planar cartography.

Done well, this served to inform players of what was technically possible (the ever-popular GM entreatment “You can certainly try...”), likely or unlikely within the world. Done poorly, it was added complexity for the sake of complexity.

The advertised endpoint was narrative immersion, but beneath that, the actual driving forces are simulationist and gamist subsystems that relied on GM fiat to bridge the gap between these systems and “the fiction.” In other words, even where the goal was to create an ongoing narrative of a sort, the prevailing play style was not explicitly narrativist.

Experience progression, escalating power within the world, or even the underutilized Humanity sub-system (VtM) are intended to function as incentive and/or avoidance loops channeling player choice within the scope of GM-prepared scenarios. These rewards resonate precisely because the simulation has already established what constitutes genuine risk and the value of earned victories, what those things look like, and what is possible in the fiction.

They also allow for a gradual expansion of scope (in terms of setting, character development etc) suited to increased capabilities.

Although it may have been under-utilized or even vestigial in some campaigns, the effects of “leveling up” or increasing stats can serve various functions in a narrative such as broadening the scope of PC concerns and increasingly embedding their objectives, risks and rewards in the story of the setting (such as where PC’s might become increasingly instrumental in the overthrow of a despotic Sorcerer King in Dark Sun, or in the War of the Lance in Krynn.)

Roleplaying games don’t present any one of these tendencies or “types” in isolation. Narrative can arise from simulationism, simulation can be expressed in gamist terms, and so on. There are potential narrative uses and consequences to many systems that are not primarily narrativist. The simple capability for a player character to fly may not in itself be a “story”, but it can have considerable impact on the types of stories you can and can’t tell. A shipwreck scenario, for example.

It’s equally useful to consider simulation’s role in fiction in general — particularly how verisimilitude and believability are constructed and sustained, especially in fantasy or sci-fi genres.

Typically, as soon as a rule has been established in-world (say that blue dragons breathe lighting) breaking that rule later must be done for a very specific reason, or else it chips away at the illusion of there being “a world” at all.

This premise carries into game design. A story lands convincingly if the world beneath it feels weight-bearing, and the outcomes in that world seem to preserve that symmetry to at least some extent. The system attempts to serve as the glue between them (the world and the outcome of new events within it).

Rules map cause to effect, the scope of actions and outcomes, etc — how far a knight travels in a day, the recoil of a pistol, what magic can and can’t do — not merely to chase realism but to preserve the fictive immersion. Verisimilitude is the result when it works.

Given a representation in consistent systems, fantasy bends physics predictably, enabling players to anticipate consequences and allowing the GM to derive drama from within believable constraints.

For many, myself included, what is “believable” in fiction is just as essential to system efficacy as behavior-driving incentives. The system to some extent needs to represent believable relationships within the fictional world. Lapses in believability can pull me out of the fiction or frustrate my immersion entirely.

These relationships can be established in the fiction first, “simply state an outcome that is believable!” but it often requires a considerable effort to front-load shared expectations in a way that’ll be mutually satisfactory. This is occasionally a sticking point for me with more narrativist systems that I otherwise am aligned with. I’ll talk about this more when I get into my own preferences and thoughts at the end of this series.

During the Trad era, the system’s responsibility to uphold simulation was often foregrounded. What was less common (at least in popular games of the era) was the element of “strict” simulation that exists in wargames. GM fiat also generally superseded the ‘neutral arbiter’ or referee style in systems that really go all in for simulationism.

In fact, holding the entire apparatus together was GM fiat — the acknowledged authority to adjust, ignore, or invent rulings whenever dice outcomes threatened the planned narrative beats or the setting’s internal consistency. Through the later-developed GNS lens, this stacks “story” atop mechanics rather than embedding story within them. Narrative, within the Trad framework, is intended to benefit-from rather than drive-toward.

When simulation ensures coherence and gamism creates pressure, the GM might deploy that fiat sparingly, whether to smooth out edge-case die rolls or address narrative gaps, and help sustain the fabric of fictional believability, or they might do so in a way verging on the despotic.

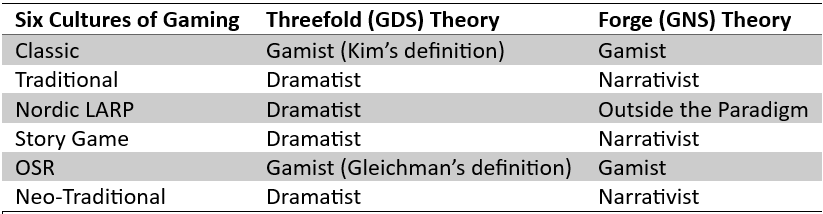

Although GNS theory can’t be either comprehensive or definitive, it remains a useful conceptual sketch for talking about these things. However, it may be most useful to consider it a hierarchy of priorities and, in some cases, an order of operations: does narrative precede or follow mechanics? Does it lead or trail system outcomes? Does the simulation implicit in a narrative carry the weight, or is it being carried by the system? To what extent? Etc.

As we’ll discuss in Part 4 of this series, later narrativist engines — such as Powered by the Apocalypse (PbtA) or Blades in the Dark — attempt to invert this sequence. They prioritize narrative beats and incentives, embrace abstraction when details hinder pacing, and endorse believability primarily as it serves thematic ends. They also tend to do so within the context of reduced GM fiat and de-emphasis of simulationist design principles.

Neither approach is inherently superior, although different people are likely to have their preferred styles, and they arguably produce different results within the caveat that a larger variable seems to be the preferences and interpretations of a specific group engaging in play. (At least I’ve yet to find that not to be the case, although it’d be nearly impossible to determine definitively).

The critical factor in either case is explicit prioritization and arbitration of control over the narrative. When players clearly understand which question the system answers first, friction diminishes, allowing that system to perform its core function: such as safeguarding the shared illusion while steering the direction of collective creativity.

Strict Taxonomy Applied to RPG Game Design: If you’re not at least a little confused, you’re not paying attention.

The Ever-turning Wheel

In summary, the rise of the Traditional style brought more structure and pre-planning into RPGs. The system side grew in complexity (to support detailed settings, richer character options, and lengthy campaigns), but paradoxically the style often de-emphasized strict rules adherence in favor of narrative coherence.

This latent tension did not go unnoticed. By the late 1990s, some designers and theorists would critique Trad play as “incoherent.”

Ironic.

(This critique was voiced famously by Ron Edwards in his 1999 essay System Does Matter, and later encapsulated in the GNS theory framework which labeled such mixed designs as flawed.)

From this viewpoint of then-emerging RPG theory, many traditional games were a muddled mix of design goals — a bit of drama, a bit of simulation, a bit of gamist challenge — which weren’t aligned with their stated goals.

A game might advertise that it’s about dramatic storytelling yet dedicate 75% of its rule pages to combat tactics. Why, asked the critics, are groups having to ignore or fight the rules to get the experience they want?

Furthermore, observers noted that in Trad play, a lot of creative effort was spent working around the rules to get the desired story. And so came the inevitable question: Instead of ignoring or bending rules to enable a certain style, why not design rules that naturally produce that style?

This question drove the next era of RPG innovation. By the turn of the millennium, a new movement was brewing — one that would argue for games built from the ground up to support their narrative or thematic goals, so that GMs and players wouldn’t have to choose between story and system. That movement, spearheaded by online forums like The Forge, would give rise to the “Story Games” revolution of the 2000s — the topic of our next installment.

Further Reading, Part 2:

Game Studies Study Buddies, “The Elusive Shift”: discussion of Jon Peterson’s The Elusive Shift: How Role Playing Games Forged Their Identity.

Gary Gygax, “D&D, AD&D and Gaming” (Dragon Magazine #26, 1979): Gygax’s own explanation of why AD&D was created – to bring uniformity and structure.

Ron Edwards, “System Does Matter” (1999): An essay critiquing Traditional RPG design as often incoherent and arguing that mechanics should directly reinforce the game’s intended style. This piece foreshadows the indie design movement that followed the Trad era.

Shannon Appelcline, Designers & Dragons (2014): The ’80s and ’90s: A detailed history of RPG companies in the 1980s–90s (TSR, White Wolf, etc.), providing commentary on how products like AD&D 2E and the World of Darkness line shaped RPG play culture.